Hand-eye coordination in young goalies (2016-2018): why train it off-ice?

- 4 minutes ago

- 4 min read

With the youngest goalies (2016–2018), one thing is always obvious: the desire is there, the courage is there, the instinct is there. What isn’t stable yet—and that’s completely normal—is the ability to make the body “answer back” with precision and consistency. At this age the nervous system is developing fast, which is exactly why it’s such a valuable window to build strong coordination foundations.

Among the most decisive skills is hand–eye coordination. It’s not a detail and it’s not “just a game”: over time it becomes the base for clean catches, rebound control, a stable glove, and an active stick. In practical terms, it means seeing a stimulus early, tracking it, reading its path, reacting, and bringing the right hand to the right point at the right moment.

The reason why, with 2016–2018 kids, I like to do a lot of this work off-ice is simple: on the ice, even when a drill looks “easy,” the amount of information a young goalie is processing is huge, a child has to manage too many variables at the same time: balance on skates, glide, posture, foot position, the type of shot from a teammate, bounces, how the play develops, the choice of save technique, and timing. The result is that attention gets diluted: pure coordination isn’t trained with real quality, the child often switches into survival mode, and frustration increases.

Off-ice, instead, we can drastically reduce variables and create a more controlled environment. Without skates and without the complexity of the game, the child is more stable, can repeat the same objective many times, and—most importantly—can focus on one single chain: see, interpret, and react with the hands. That’s where quality truly goes up, because learning happens through “clean” repetitions, with full focus on the coordination task.

This approach is consistent with several principles of training and motor learning. On one side, there’s the idea of sensitive periods: between roughly 6 and 10 years old, the brain absorbs and organizes motor and coordination patterns very quickly, so investing now in these basics pays off massively in the medium to long term. On the other side, there’s the progression from simple to complex: first I stabilize a skill in a low-complexity context, then I gradually add “noise” and variables until I bring it back onto the ice, where balance, glide, shot reading, and decision-making come into play.

There’s also a factor that’s often underestimated: cognitive load. Children have a limited capacity to handle many pieces of information at once; if the load goes above their threshold, attention drops and movement quality gets worse. Off-ice allows me to reduce that load and create the conditions for more effective learning. And in the goalie position, coordination is always a perception–action coupling: it’s not enough to “move the hands,” you have to connect what you see to what you do. Off-ice work with clear, progressive stimuli helps build that connection in a solid way.

Finally, to truly learn, it’s not about repeating the exact same thing forever; it’s about repeating the same objective with small, controlled variations (speed, angle, distance, dominant and non-dominant hand). That’s the idea of “repetition without repetition,” which develops adaptability and precision without losing quality. Alongside that, I often use a constraints-based approach: instead of giving a thousand corrections, I set distances, time limits, object size, movements or bounce characteristics that naturally guide the movement and help the child find the right solution, because coordination hasn't a single option to be applied, it is a quest that every single kid need to make and adjust on his own structure.

With young kids, my goal isn’t to create “mini-pros” or chase the perfect save. The goal is to build foundations: confidence, curiosity, movement quality, and strong coordination basics. If those foundations are trained well today in a controlled context, tomorrow—when we add all the variables of the ice—the child won’t go into overload. They’ll already have a coordination “software” ready to build on.

Training hand–eye coordination off-ice for young goalies isn’t an extra. It’s an investment. Fewer variables, more focus, more high-quality repetitions—and above all, a child who learns while having fun, without stress, with real progress.

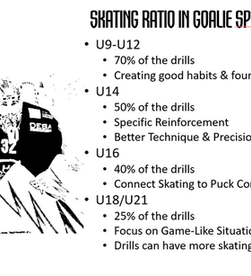

To make that development even clearer, I like to structure the pathway in phases. In the first goalie season, the focus on the ice will be only on skating, basic technical skating, and the essential saves. This approach may not always satisfy every coach in the short term, but it allows us to build a more even and faster overall progression.

Then, during the summer break between the first and second season, we’ll dedicate targeted time to hand–eye coordination and a few other small details—still in a controlled environment—so that from the second season onward a more specific style can start to take shape for the young goalie.

We can’t think of an 8-year-old goalie as if they were a professional. Even today’s pros had to learn from the basics, and that learning becomes faster when we remove the “noise” of too many other things at the same time.

Comments